Mangrove restoration that works: lessons from Rassam from Lamu

Rassam Mansur was born in the coastal city of Mombasa, Kenya. But his first encounter with mangroves wasn’t outdoors or in a classroom. Rassam was 9 years old when the 2004 tsunami struck. His family was supposed to go to the beach that day but instead they stayed home, heeding warnings from the Kenyan government. “I remember asking my mother why there wasn’t much impact in Kenya,” he recalls. “My mother is not a learned person. And though her reasoning was flawed, what she said stuck with me. She told me, ‘Coral reefs and mangroves are the guardians of our coasts.’”

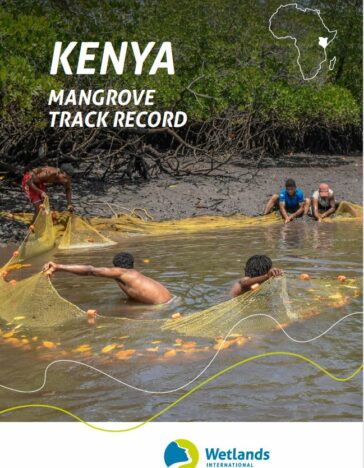

That simple statement sparked a fascination. Years later, Rassam moved up the Kenyan coast to Lamu, a place where mangroves aren’t just guardians, but they are providers. “We are a marine people,” Rassam explains. “We rely on mangroves for food, fuel, and building materials. We even export mangrove wood to other regions of Kenya.” But Rassam doesn’t love mangroves for what they give but rather what they are. “They are so quiet and peaceful yet bursting with life. It’s like being in a world within a world,” he says.

But over time, the harvesting of these mangroves took a toll and the degradation Rassam saw broke his heart. Committed to reversing the damage, he led a group of 15 of his family and friends that set up nurseries, grew seedlings, and planted them. For years they attempted to revive the mangroves by planting, but their efforts failed repeatedly as most of the seedlings died. “I didn’t know why this kept happening, but I was beginning to lose faith,” he says.

Then fate intervened.

Everything changed in 2022 when Wetlands International and Mangrove Action Project introduced a few community members to CBEMR—Community-Based Ecological Mangrove Restoration. Among those trained was Rassam’s mother-in-law, who immediately shared what she learned with him – that the majority of mangrove mass planting efforts fail. Though well-intended, without knowing the underlying conditions of the area, planting can fail because the wrong species of seedlings might have been used, or the hydrology of the area was never restored. CBEMR, however, relied on community members understanding the root cause of degradation and applying relevant solutions to ensure the natural regeneration of mangroves, ensuring their long-term survival.

In early 2024, Rassam crossed paths with Wetlands International again—this time more deeply involved. Wanting to avoid previous failures with mass planting, Rassam insisted the Wetlands International team assess mangrove dieback in a waterlogged site in Muhogoni (on the outskirts of Koreni Village, Lamu). The community, including Rassam, alongside Wetlands International determined the cause to be sediment flow that blocked natural water channels. Rassam and a group of thirty individuals spent four days unclogging the waterways. “We used the simple tools we already owned – spades and jembes (hoes),” he said. The group returned to the site four months later to continue their restoration efforts and found some natural regeneration already taking place. With the waterways restored, mangrove seedlings dispersed widely and had room to grow. Rassam now often visits the site both to monitor the success of his work and for his own recreational activities. “The change I’ve seen is amazing,” he comments. “Though there is much more to be done, CBEMR restored my mangroves and my faith.”

“Mangroves are our mute and mortal messiahs,” he states. They cover only 0.1% of our planet but we cannot survive without them.

Rassam now serves as the Secretary of the Mkunumbi Community Forest Association where he urges his community members to take ownership of the wellbeing of their mangroves. “Mangroves are like your spouse,” he jokes. “If you have a good understanding of them, you’ll live together in peace.”

On a more serious note, he calls on NGOs and others to help develop alternative livelihoods for his community. While CBEMR has proved successful, natural regeneration takes time. “We need sources of income that don’t depend on us cutting down the mangroves,” he says.

“Mangroves talk to us,” he concludes. “All we have to do is stop and listen.”

For more information about our work to restore and conserve mangroves in Kenya, introduce alternative livelihoods and create an enabling environment for scaling up our best practices, read the publication below.