Time travel with wetlands

-

Climate and disaster risks

-

Climate mitigation and adaptation

-

Coastal resilience

-

Community resilience

If we could travel back in time, to the year 1900, 65% of all wetlands in the world would not yet have been lost. We would have better flood control, fewer droughts, clean water, less carbon emissions, plentiful food and fish and beautiful nature. It might not be possible to go back in time, but we have a lot more knowledge today to restore many of our wetlands, and do more to safeguard those that are still in a healthy state.

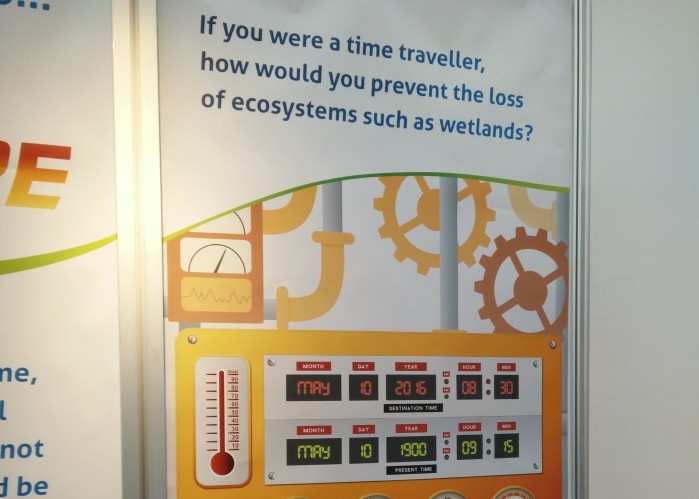

Last week, at the Adaptation Futures conference in Rotterdam, we triggered people to think about the future, and the past, and what they mean for wetlands. We had our very own time machine installed at our booth and asked everyone who came to our booth to step inside and tell us: If you were a time traveler, how would you prevent the loss of ecosystems such as wetlands?

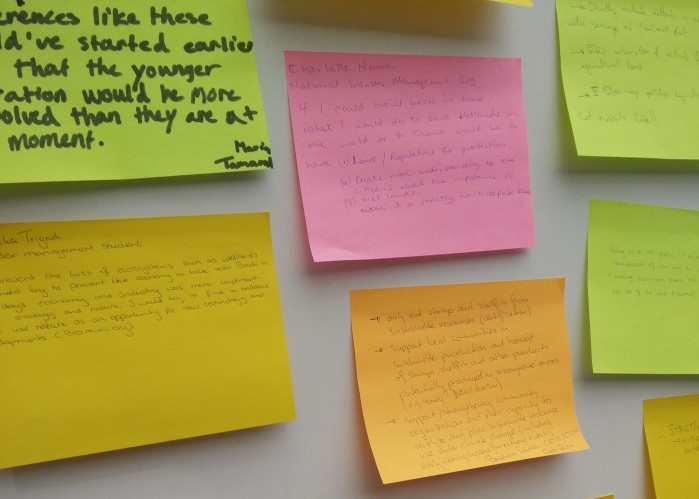

The responses were diverse and interesting, but some common themes emerged. For example, the importance of educating young people. Raisa Banfield, the Vice-Mayor of Panama City stepped into our time machine and told us: If I were in 1900 I think I would start with the education of our people. In the beginning of our development we didn’t know anything about wetlands and how important they are. So I would start with educating our kids.

Another time traveler agreed: I would make sure that the education system includes teaching children to live with nature, and knowing how to safeguard its intrinsic value and ecosystem services instead of living beyond our limits! Children embrace what they learn and put it into everday practice. Children embrace what they learn – what a great message for educators and anyone in a position to inspire young minds.

Ruth and Charlotte from Ghana, Bastiaan from Costa Rica and Amar from Perth all pointed out that they would enable early involvement of the people that directly depend on wetlands in decision-making, as well as strengthen community organisations to analyse and plan sustainable resource use in the face of climate change.

Many also pointed to the importance of economic factors. Harma from the Netherlands stated: In business planning, besides economic costs and benefits, social and environmental costs and benefits should also be included. Annika, a water management student from the Netherlands: I would try to prevent the economy taking over. Back in the day, economy and industry were more important than ecology and nature. I would try to find a balance and use nature as an opportunity for new technology and development.

The conference was held in the city of Rotterdam and adapting cities to climate change was a central theme of the conference. Urban wetlands were also mentioned by a number of our time travellers, including Raisa Banfield: at that moment [1900] Panama was just a little city and a huge rainforest, with wetlands, but we started to build without planning and thinking about it. So start thinking and planning. Roger from Spain also highlighted the importance of urban wetlands: If I could come back to the 1900s I think I would protect the wetlands in the urban areas because that improves substantially resilience in the case of extreme events.

However, perhaps my favourite response came from Tuhin from India: Consider the Ganges–Brahmaputra-Meghna Delta, and travel from East to West: you can find the present scenario in the East, near future in the Middle, and far future in the West, while crossing the international boundary between Bangladesh & India…. Is this not a time machine!?

I thought of what Tuhin had written as I took the train home from Rotterdam. During the train ride we passed a typical Dutch scene: a polder with an old windmill, its blades turning against the lowering sun. It was a picturesque scene. Further on along the tracks we passed another field full of wind turbines: sleek, modern and minimalist. These structures are considered an eye-sore by many. Yet here is a story of the past and present written on the landscape, just like the story Tuhin sees in the Ganges Delta.

I can now imagine a future in which those wind turbines will be seen as beautiful, a future in which their white blades will still turn, but not because they need to. In this future we will have come up with even better, smarter ways to generate energy. It is also a future in which we will be much smarter about ecosystems, in which wetlands will be protected, invested in and fully able to play their vital role in the landscape.