Can wetlands save Saint-Louis from drowning?

-

Climate and disaster risks

-

Coastal resilience

-

Coastal wetland conservation

-

Community resilience

-

Integrated delta management

The Senegal River is the second largest river in West Africa and forms the natural border between Senegal and Mauritania for much of its course as it flows west towards the Atlantic Ocean. At the coastal delta it flows past the low river banks of the city of Saint-Louis. From there it turns south, running alongside a thin strip of sand dunes separating it from the ocean for the last 30 km until it reaches the river mouth.

Saint-Louis is the former capital of Senegal and French West Africa. Often called the ‘Venice of Africa’, for its setting in the river delta, it now carries the distinction as the city most threatened by climate change in all of Africa.

The city has a history of flooding and is increasingly at risk of drowning due to heavy rain events and rising sea levels. In 2003, intense rains overwhelmed upstream dams. Man-made dykes constructed along large parts of the upstream riverbanks severely limited the natural outflow of water into the surrounding wetlands and floodplains. The huge volumes of water coming downstream created a crisis in Saint-Louis. The heavy flow could not reach the mouth of the river quickly enough due to bottlenecks downstream of the city. Instead, the river backed up and the rising waters threatened Saint-Louis. To save the city, a new channel was quickly excavated through the sand dunes, 10 km downstream of Saint-Louis, creating a shortcut to the ocean that immediately relieved the pressure and eased water levels.

The breach and coastal erosion

This hasty solution succeeded in getting water off of the land and out to sea, but it created its own set of unintended consequences that are increasingly urgent problems. For starters, what initially was a four-metre emergency channel within weeks became a permanent bypass 400 metres wide. Exposed to the forces of nature from both sides – heavy surf from the Atlantic Ocean coming from the west and the river flowing from the east – today the breach is now 5.2 km long and still growing.

To the north the ocean has swallowed two villages and is threatening more. The southern half of the sand-dune barrier is now an island that is home to Langue de Barbarie National Park. This popular UNESCO World Heritage Site and bird sanctuary is notable for large numbers of breeding gulls and Royal Terns, and serves as the most important egg-laying beach for Green, Hawksbill, Leatherback and Loggerhead sea turtles in Senegal. The entire park is in danger of disappearing due to erosion.

The breach and loss of the flood pulse

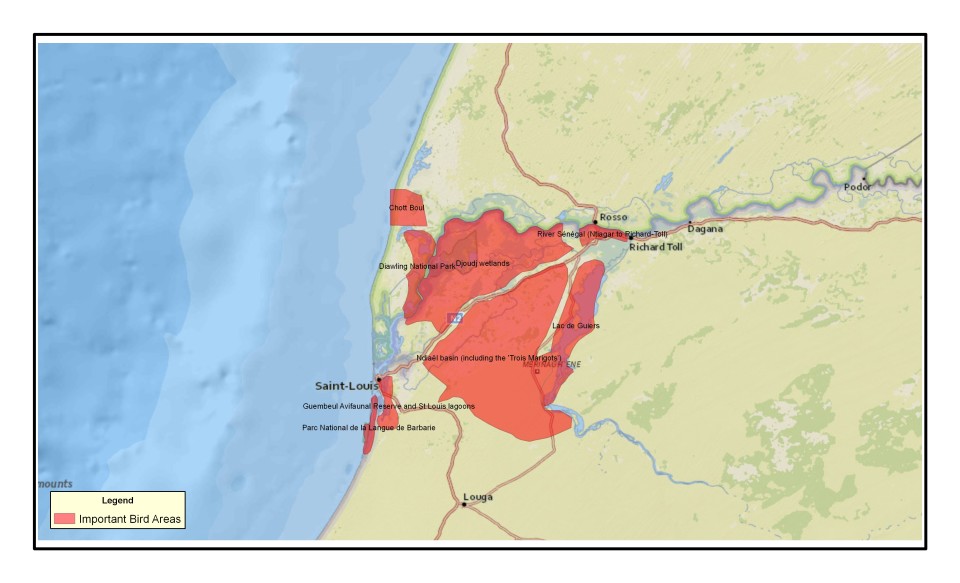

Stopping the spread of the breach and protecting threatened communities is the most immediate challenge to tackle. However, the negative impacts of the breach, combined with rising sea levels, are being felt across the landscape. Saint-Louis is situated in the lower Senegal river delta, surrounded by several outstanding parks and reserves within the Senegal Delta UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve. These natural areas are suffering, due to a combination of the breach and upstream infrastructure, as are the nearby communities. Before the breach was created, these areas benefited from an annual flood pulse – a temporary inundation of the floodplains that brought freshwater to an otherwise parched landscape. Without the flood pulse, there is less freshwater, salt water is intruding upstream due to a larger tidal pulse, nature is suffering and the food security of local communities is at risk. For example:

- Diawling National Park in Mauritania is a Trans-Border Biosphere Reserve that sits across the river border from Senegal’s Djoudj National Park. Both parks are home to spectacular bird life, and until 2002 there was a huge coastal plain on the west side of Diawling that received an annual flood pulse. This one to two month inundation spilling over from the Senegal river benefited both birds and the local communities with their grazing animals. Since the breach in 2003 water no longer backs up enough to flood the park’s western floodplain, and it is now a large, dry, sandy plain that supports neither the park nor the people living around it.

- Guembeul Special Wildlife Reserve is south of Saint-Louis and downstream of the breach. It is an important site for waterbirds and the reintroduction of Sahelian wild species, including three species of gazelles. The wildlife inhabiting its mudflats, lagoons, mangroves and forests used to benefit from an annual freshwater flood pulse. Post breach, this inundation no longer reaches the reserve and freshwater levels are dropping and the mudflats are staying dry, to the detriment of wildlife.

- Trois Marigots in the Ndiaël basin lies in the Senegal river floodplain 60 km northeast of Saint-Louis. The annual flood pulse of the river used to reach these three parallel marshes, separated by sand dunes, that are part of an Important Bird Area. When flooded these temporary lagoons attracted large numbers of waterbirds and support local livelihoods based on farming, fishing and pastoralism. Without the flood pulse the lagoons are no longer there, only desert.

Looking for long-term solutions

Instead of another quick fix that creates even more problems, there was a recognition by the government of Senegal that a different approach was needed. In 2014 Senegal requested advice from the government of the Netherlands, and a special Dutch Risk Reduction Team was dispatched to assess the situation and provide advice. This cooperation is an opportunity to look at larger scale, long-term solutions to the region’s coastal problems. With financing provided by the World Bank and European Union, the next step is an integrated study of the lower delta that seeks to understand how it functions, including the value of floodplains for nature and food production. Beyond the technical aspects, stakeholders – including local communities – will be consulted on their interests.

Making Room for the River

What once seemed to make sense – getting floodwaters off of the landscape and away from Saint-Louis as quickly as possible – is now worth revisiting. While Saint-Louis is still threatened by rising waters, this is an increasingly water-scarce and thirsty region buffering the Sahara Desert to the north.

In thinking about the floods and droughts to come, Wetlands International is asking, how can wetlands help protect Saint-Louis from flooding? And can storing water in the lower Senegal Delta wetlands contribute solutions to the region’s water scarcity and food security challenges?

We have extensive experience in Building with Nature solutions around the world. We look forward to contributing our ideas and expertise in the Senegal river delta to think about how a combination of wetlands and infrastructure can best be used to restore the flood pulse and protect Saint-Louis and the wider coastal region.Instead of sending the floodwaters directly out to sea, why not make more room for the river within the floodplains by restoring the flood pulse to water-starved areas of Diawling, Guembeul and Trois Marigots? We are proposing an approach that will reduce flood and erosion risk in the coastal areas around Saint Louis, and at the same time restore important wetlands to benefit biodiversity, livelihoods and rural development.