A first look at the 2020 International Waterbird Census

-

Asian Waterbird Census

-

International Waterbird Census

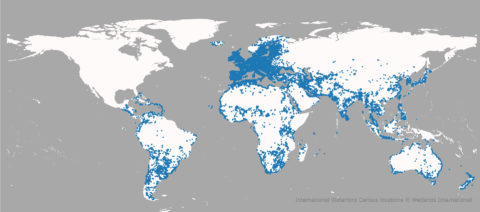

Thousands of birders joined our annual International Waterbird Census last month, monitoring waterbirds around the world. First organised in 1967, the census now covers over a hundred countries, making it one of the largest and longest-running biodiversity monitoring programmes in the world.

Counting waterbirds is important for wetland management

Traditionally, wetlands have been viewed as wastelands – little more than breeding grounds for mosquitos and an opportunity for coastal land reclamation, which has dramatically reduced the amount and quality of habitat available to waterbirds. However, as the demand for water, land and food increases, they have become the ecosystems most in decline in the world.

Counting waterbirds allows us to see whether a wetland is under threat. Our monitoring is the foundation for managing and understanding wetlands. It has helped species and populations that were once in serious decline to make remarkable recoveries.

An astonishing 1.7 million waterbirds counted in Banc d’Arguin

This year, the IWC included an expanded count along the Eastern Atlantic coast, building on similar significant efforts in 2014 and 2017. These individual count years provide data for regions where an annual census is impracticable, such as the large and complex sites in Western Africa, where large teams are required for accurate monitoring.

A highlight this year was an astonishing count of 1.7 million waterbirds in the famous Banc d’Arguin in Mauritania, which host a large proportion of the coastal waterbirds along the East Atlantic Flyway. Banc d’Arguin is recognised worldwide for its marine biodiversity and its globally significant wild bird population. This effort was coordinated internationally by the Wadden Sea Flyway Initiative, BirdLife International, Wetlands International West Africa and the Wetlands International Global Office.

Our results from other major waterbird monitoring initiatives

Africa and Eurasia

The IWC in the Western Palearctic ran alongside the quintennial International Swan Census, coordinated by the Wetlands International / IUCN SSC Swan Specialist Group. The internationally coordinated swan censuses not only gives invaluable information on trends in numbers for each population but, by aiming to count all swans at their wintering sites, provide the total population size. These data are used to determine sites of national and international importance for the species.

They also describe any major shifts in site or habitat use over time (including areas not covered by the IWCs) and provide a comprehensive measure of the percentage of juveniles in flocks across the wintering range. Traditionally the Swan Census covered Western European populations of Whooper swans and Bewick’s swan (the only species protected under EU Annex 1 and which IWC data shows to be in long-term decline).

Neotropics

The census in the Neotropics started earlier this month (February). The Wetlands International Latin American and Caribbean office in Argentina has begun collaborating with Aves Argentina and the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network to run a Wilson Phalarope Census during the first ten days of February. By communicating the significance of this census to regional coordinators, the coordinating team aim to obtain more detailed information for the species beyond the standard site count, which will ultimately help in assessing habitat use as well as global population estimates and trends.

Caribbean and Central America

Regional waterbird censuses have been organised for the Caribbean by Birds Caribbean and for Central America by Manomet. The Central American surveys will have tenth anniversary in 2020. These surveys will continue until mid-February. The Caribbean census finished in early February.

The results of the multi-species trends and supporting information can be found here.

Without the IWC, we would not be able to provide immediate action and the proper management, and these precious ecosystems would be destroyed, with tragic consequences for human livelihoods, biodiversity and climate adaptation. With this data, we can also categorise important non-breeding sites where migratory birds can rest before embarking on the long journeys back to their breeding grounds.